The Aweful Platonic Mystery That Burns at the Heart of All Games

I've always been a fanatic about games. What we might call classical table games— the games that grow up more or less spontaneously out of a culture, and are played sitting at a table with special equipment. Board games. Card games. Throw in various tile games and dice games, too.

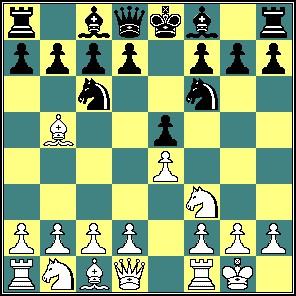

I learned chess at an early age. Checkers too, of course. And backgammon. Chinese checkers. Parcheesi. Nine men's morris. All these board games fascinated— no, more than just fascinated me. They drew me. Drew me with a magnetic attraction toward some hidden, uncanny polar magnetic north.

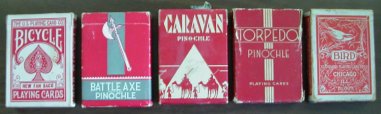

It was the same with playing cards. I started learning card games before I was in school. Then in grade school I discovered an edition of Hoyle's Rules of Card Games. Other Hoyles out of the public library. And I proceeded over the years to learn one card game after another, straight out of the book. Euchre. Cribbage. Pinochle. Five Hundred. Canasta. Poker. Rummy. Gin Rummy. Bezique. Cassino. Cinch. Pedro. Black Jack. Faro. Sheepshead. Skat. Piquet. Auction Pitch. Oh Hell.

I remember when I was nine, sitting there and playing bezique with my dad, who was sick in bed. (Some version of bezique, I forget which, was the favorite card game of Winston Churchill.) There was something about playing cards which drew, almost mesmerized me. Yes, the bright colors, the curious designs. Yes, the thrill and the strategy and the Gemütlichkeit of a good game of cards. But there was something more to it than that. Some aweful, awesome, burning mystery which was glimmering through the cards and their play, like some whispered clue to a vast and hidden realm.

It almost felt to me, with card games and board games, like I was entering some alternate level of reality. To be immersed in a game of chess, sheepshead, nine men's morris, two-handed pinochle, was to be steeped in something like another world. A world bathed in an unearthly light. A world perfused with some ineffable secret.

I found the same in dice games as well. And in tile games like dominoes and Mah Jongg. I didn't find it in most proprietary games, like Monopoly or Stratego, even though I enjoyed playing these. And I had (and have) virtually no interest in sports. But classical board games and card games were another matter.

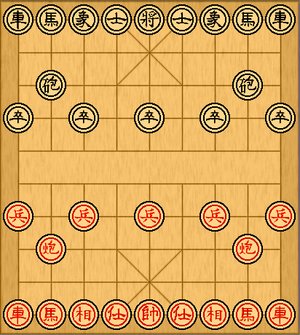

Then around age 14 or 15 I discovered a Dover reprint of Edward Falkener's Games Ancient and Oriental and How to Play Them (1892). And I absolutely went nuts. The game of Shogi, or Japanese chess! Siang K'i, or Chinese chess! Tamerlane's chess! Here were board games more alien and more wondrous than anything I had ever imagined!

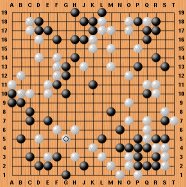

There weren't many books like this available back in those days, but I hunted down what I could find. John Gollon's Chess Variations, Ancient, Regional, and Modern: I had correspondence with Mr. Gollon concerning a fine detail of the rules of the game of Jetan, or Barsoomian chess, out of Edgar Rice Burroughs' The Chessmen of Mars. Several books on Shogi, Mah Jongg, and the game of Go. And a hardcover reprint of H.J.R. Murray's classic A History of Chess (1913)— I can remember literally dancing for joy the day that book arrived in the mail!

In high school art class, I made sets for many of these exotic board games. Boards were generally leather (it helps to have an uncle who was a salesman for a leather company). Pieces were cannibalized, recombined, and spray painted from various store boughten Staunton chess sets, or in some instances hand made.

I eventually did manage to find store boughten Go and Shogi sets. It was hard to find such things. It was hard to find anything on such games. Games like these were much further out of the cultural mainstream 30 years ago than they would be today.

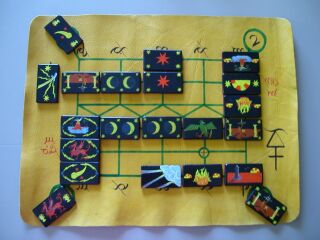

From a certain age on up, I also started making up board games and card games of my own. Some, like my game of Blue Pinochle, were "in the ballpark." Some, like the Quintuple Arcana (in my own Hermetic language, Mna Jondir-Pantho Zinisa) were like nothing you've ever seen or heard of before— above is the Quintuple Arcana set I made in my college years.

From early on up, I collected playing cards. Ended up with a collection which today amounts to hundreds of card decks. I also haunted the used bookstores for books about board games and card games. These today fill two large bookcases, and include such curiosities as an old Hoyle printed in Philadelphia in 1838 by Thomas, Cowperthwait & Co.; H.J.R. Murray's A History of Board Games Other Than Chess; Foster's Skat Manual; Cavendish on Piquet; Fukumensi Mihori, Japanese Game of "Go" (Board of Tourist Industry, Japanese Government Railways, 1939); Von Leyden, Ganjifa: The Playing Cards of India; and a crumbling booklet on Four Chess, a four-handed chess variation, printed by the Senior University Chess Club, Cambridge University, 1892.

But the main thing is, that aweful Platonic mystery that burns at the heart of all games. I can set up one of my board games, and just sit there meditating on it, literally for hours. Or sit there imagining possible moves of unheard-of mutant chess pieces, or board games curious and unconceived.

I often have dreams about strange unknown board games or card games, or finding unusual card decks in a heretofore undiscovered secret room in the house. Sometimes these dreams find their way into reality: when I was only seven, I had a dream about a chess variation where one chess piece enabled other pieces on the board to have special moves when they were in alignment. This feature later found its way into a chesslike game I invented.

Games aren't the only thing that can trigger that uncanny feeling within me, that sensation as if of being connected to some alternate reality. I've always found a similar experience in listening to the radio. I don't know quite what to make of it, I've never known anyone else who has such a reaction to such specific cues. It seems almost like an abstract form of synaesthesia.

Labels: best_of, doors_of_perception, games

2 Comments:

Actually, I respond to quilts, color combinations, and certain literature the same way.

Personally, I'm sure that James Joyce naturally tapped into some sort of pattern or formula to create some of his greatest works, and that if we could only see the pattern we could all write that well.

Much the same way that Einstein was convinced that anyone could compose like Mozart once the formula was known. Its my understanding and memory (which is questionable due to child-induced-sleep-dep) that if you asked Einstein for a profession he would consider himself a musician who justified his obsession with science as merely an ends to discovering Mozart's formula.

Of course, Einstein was gifted enough to embark on a quest for the formula and I'm content to merely acknowledge the concept while I'm making PB&J for everyone's lunch!

Lucy, yes, that formula comes through in the abstract structures of mathematics, too.

In fact, that brings back a conversation I had many, many years ago, with a fellow grad student in math, about how the glory of God shows through in quaternions and Cayley numbers.

Post a Comment

<< Home