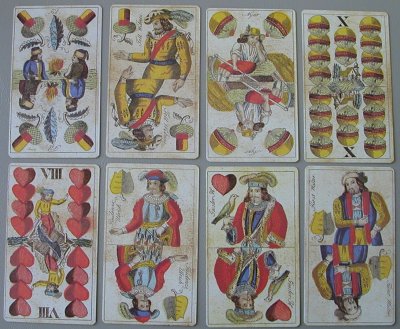

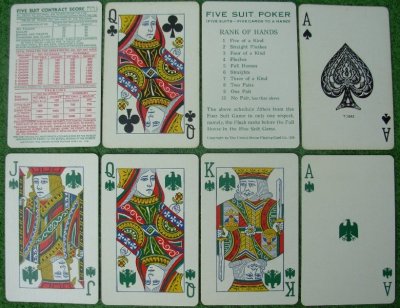

The Quintuple Arcana

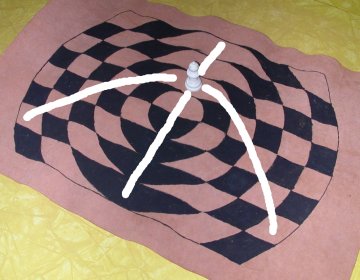

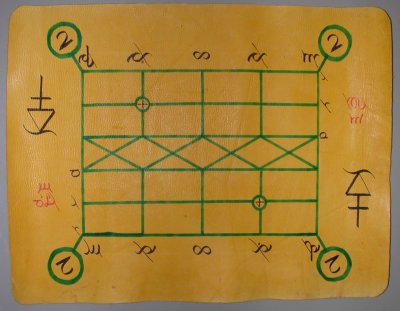

Fig. 1 The Quintuple Arcana

Given my lifelong fascination with games, it should come as no surprise that I've made up a number of games of my own. I've got one game, in fact, that I've been working on for over 30 years, and I'm not finished with it yet.

It's called the Quintuple Arcana— in my own Hermetic language, Mna Jondir-Pantho Zinisa. The Quintuple Arcana is one of the chief board games played by my Hermetic people, though the game was originally created by an alien race called the Esloniki, in the science-fictional future history I was writing back in my teens. I've got to be careful here— in my mind, much of the terminology for the game is in Hermetic. Will try to render it into English as I go.

The Quintuple Arcana is a game for two players, played with tiles which are entered and moved around on the board. Each player tries to move so as to form certain melds, or combinations, with his tiles. It's sort of like playing Pinochle, or Mah Jongg, only it's a board game. Some melds enable capture of an opposing tile (think Nine Men's Morris). Some melds score points. Some melds hedge in or block the opponent. Some melds open up transitions to new states or levels of the game.

And then there's all the extra, incredibly intricate rules and exceptions to rules. The rules of the Quintuple Arcana are so mind-bogglingly complex, they make Chess seem like

I started working on the Quintuple Arcana at age 18. At first it was just vague wisps drifting across the back of my mind, like colored tissue paper wafting on the breeze. Bits and pieces and dimly-beheld snatches of the way this game of games ought to be. I had to get into just the right meditative frame of mind, into a state of flow; and even then I couldn't force it, the game just came to me, a detail here, an exception to the rule there. I must've been doing something right: after a while magic squares and other mathematical surplusage began dropping out of the rule structure unbidden.

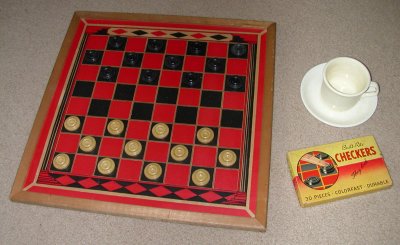

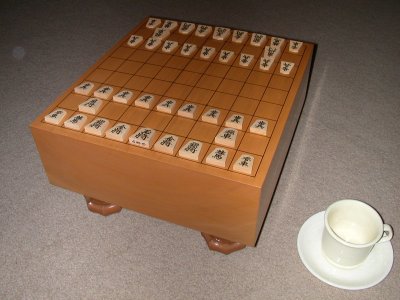

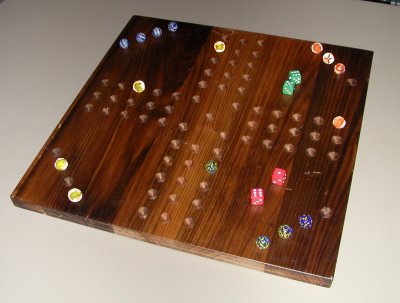

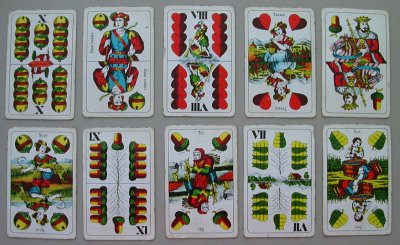

Fig. 2 The Quintuple Arcana Board

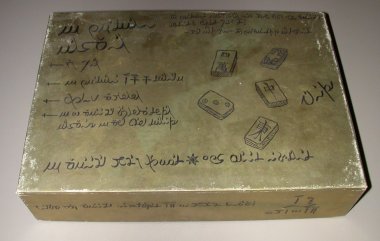

The board for the Quintuple Arcana is made of yellow leather, marked in green and black and red. In the middle of the board is a cross-hatched area, called the Confluence (think Chinese Chess). The two players are known as Red and White, and each player stays on his own side of the Confluence.

Each player has eighteen points on which to play and move his tiles: fifteen points of intersection, a three-by-five grid known as the Quinquedecade; plus three other points known as Stations, one in each corner and one off to the right-hand side.

The points of the Quinquedecade fall into five metals and three colors. The metals, starting from each player's left hand and moving across to the right: quicksilver, silver, copper, gold, and iron. The colors, starting closest to the player and moving up toward the Confluence: green, blue, and red. Silver and gold are the stronger metals, and red is a very strong color. A meld formed on red is very powerful, but also more vulnerable. The specially marked point on gold at blue is also known as the stone point: associated with it are certain privileges and restrictions of move.

Note how Red's quicksilver is located right across from White's iron, and Red's silver right across from White's gold. Red's copper and White's copper stand across from each other, which leads to special rules for when one player already has a certain tile on copper, and the other player tries to move an identical or similar tile to copper.

The two corner stations, indicated by large circles, are known as the yellow stations. Tiles moved to the yellow stations tend to alter rules and rankings across the board. The color of these stations is yellow, the metal of these stations is wood. For purposes of tile movement, these stations are not considered as being diagonally behind the Quinquedecade, but rather as the color behind green, or the metal next beyond quicksilver or iron.

The station to the right of the Quinquedecade is represented by an old Eslonikese syllabic sign, and is known even in Hermetic by its old Eslonikese name of the cra, that is, the mode, or the state of being. The cra is invested with certain powerful immunities, and tiles in this station extend some of those immunities across the board.

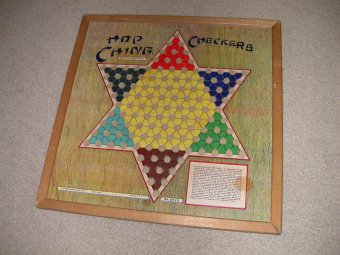

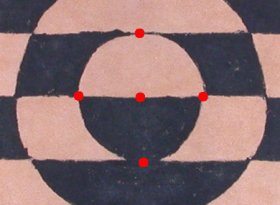

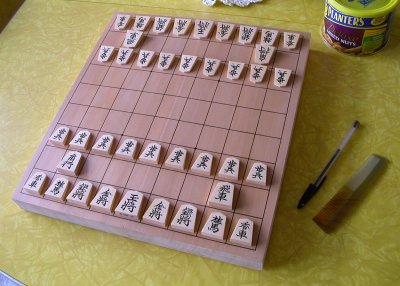

Fig. 3 The Quintuple Arcana Tiles

Each player has two dozen wooden tiles, black enamel with red felt on the underside. The tiles are divided into three categories: number tiles, suit tiles, and odd tiles.

A player has two each of number tiles from one through five. One is a green eagle bearing a crozier and a thunderbolt. Two is two crescent moons, to Hermetics the twin moons which govern the rainfall. Three is three beams of sunlight shining through the clouds. Four is an Esloniki working a ritual, holding a torch over a basin of water between the two pillars of the four elements. Five is five heptalphas or seven-pointed stars.

The suit tiles fall into three suits, urns, suns, and lightning. Each suit has four ranks, suit signs (low), volcanos or firesprings, dragons, and comets (high). In the suit of suns, the phoenix replaces the dragon. And in the rank of suit signs, the suit itself becomes the rank. Under special conditions, the rank of suit signs can "pivot" to become a fourth suit, the suit of heptalphas or seven-pointed stars.

The names of the twelve suit tiles, in English, are urn comet, sun comet, lightning comet; urn dragon, sun phoenix, lightning dragon; urn firespring, sun firespring, lightning firespring; burning urn, rising sun, thunder sword.

The two odd tiles are the tower and the eclipse. These are used to alter the legal moves of other tiles aligned with them on the board, the tower extending the moves of one's own tiles, the eclipse blocking one's opponent's tiles.

The rank of the tiles, as well as the tiles constituting a meld, can shift radically according to the "conditionalization" of the board, influenced chiefly by tiles in the yellow stations. For example, in (default) five-hexatonic mode, a meld known as the major sequence consists of the three number tiles five, four, three, arranged in any order in a straight line on any three adjacent points of the Quinquedecade. But in three-hexatonic mode, the major sequence consists of the number tiles three, five, two; and in four-heptatonic mode, the major sequence is four, one, three.

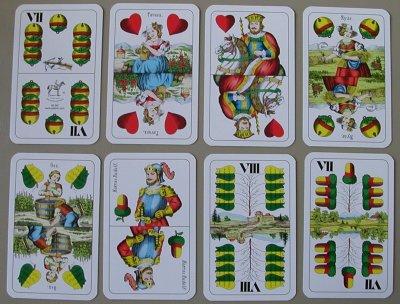

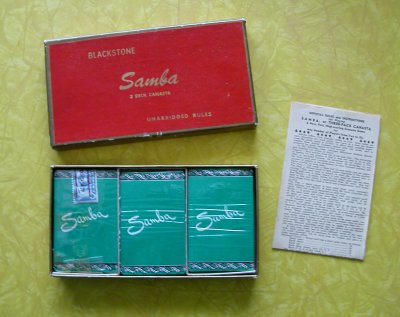

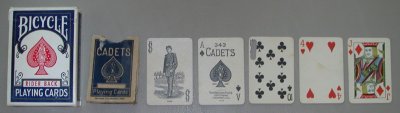

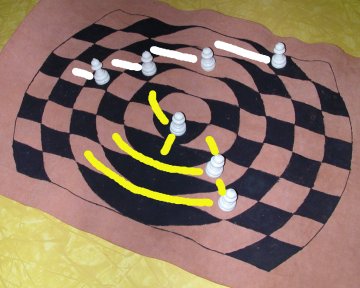

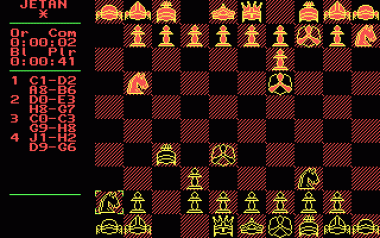

Fig. 4 The Quintuple Arcana— A Scoring Position

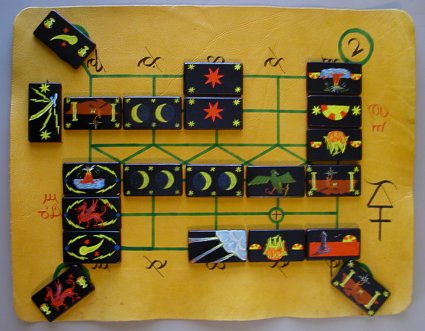

The game begins with the board empty. Red and White alternate turns, and in each turn a player may either enter, or move, or remove, or reenter one of his tiles. As the tiles build up and shift on the board, each player strives to form melds, gaining advantage for himself, or imposing disadvantages on his opponent. Play may appear to be blocked; then changing to a different mode opens up a whole new set of possible moves and melds.

In the position shown above, White scores by moving a four from the cra to iron at blue. This gives White three melds: a secondary sequence (sun phoenix, sun firespring, rising sun), vertical on quicksilver; a pair of fives, vertical on copper at green and blue; and a major sequence (four, five, two), horizontal on blue, according to the four-hexatonic mode induced by the urn comet in the yellow station.

The secondary sequence and the pair together meet the "configuration readiness" precondition for White to score by closing the major sequence with the move from the cra: advais cvadro viro sajoro, "moves four to iron at blue." White's score for his position is as follows: basic score for major sequence, 20 points; score for pair united with major sequence, 4 points; score for closing meld from a station, 2 grace; score for purity of tile (quinquedecade has only number tiles plus one suit), 20 points. No doubles means a multiplier of one, 44 points times 1 plus 2 grace equals 46 points total. Note 46 points worth of scoring bars awarded to White at bottom of board, above.

Whew! Like I say, I've been working on this game for over 30 years, and I'm not there yet. I've got a notebook densely filled with over 70 pages of rules, add in another 20 pages I've got in loose leaf and we'd be getting close to the complete rules on first level. But then the game goes to second level, and third, and... I'll never get there. I'll never get it finished. Meanwhile, on the lid of the scoring-bar box, there's me, my dog, and a Camel from outer space, watching two Esloniki playing the Quintuple Arcana, in that land where the sun is eternally rising in the west...

Labels: games